Indian cacao farmers with craft chocolate ambitions

Opening the windows of the tree house on Varanashi Organic Farms was a soothing balm. Looking out into treetops spearing the cotton-candy sky at this 100-acre family farm in Adyanadka, a village in Dakshina Kannada District, our city bones were lulled into finding their forest feet.

For the next three days, we immersed ourselves in the Cacao Residency hosted by the cacao-growing farm along with Goya, a food media company, and the Indian Cacao & Craft Chocolate Festival, a five-year-old initiative that brings together the stakeholders in India’s cacao and craft chocolate ecosystem. We learnt about the evolution in farming methods and processing techniques, witnessed the making of a craft bar, and tasted a selection of small-batch chocolates.

At a time when headlines are being overtaken by news of rising cocoa prices, and social media is warning consumers to check the label for ‘chocolate flavouring’ — an attempt by brands to find cheaper ways to keep their products on shelves — it was interesting to walk up to the oldest cacao trees in South India. Partha Varanashi, the ninth-generation farmer of this over-200-year-old property, shares how these 65-year-old trees were brought as saplings to the farm by his late grandfather Varanashi Subraya Bhat.

Numerous strains of cacao from South America and other cacao-growing countries were tried and tested for their viability and yield at the Central Plantation Crops Research Institute before settling on two hybrids. From Bhat, these saplings were distributed to other farms in the region, “and within the next five years, they were producing over 50 tonnes of cacao [sold to Cadbury]”, says Varanashi.

Partha Varanashi at Varanashi Organic Farms

In the mid-80s, however, “when Cadbury lowballed farmers on the price for cacao”, Bhat’s other founding venture, the farmers’ cooperative Central Arecanut and Cacao Marketing and Co-operative Society (CAMPCO), added another first. They decided to start their own production in Puttur. “It was then the biggest chocolate factory in South Asia,” Varanashi explains, adding that it boosted chocolate consumption in the South.

Not an ordinary chocolate bar

Today, things are very different. Craft chocolate is on the rise across the country, and in just the last three to four years, around 20 bean-to-bar makers have come up across India, states Ketaki Churi, chocolatier and co-founder of the Indian Cacao & Craft Chocolate Festival. “Most of the small-batch, craft chocolate brands emerging, especially in South India, are from cacao growers themselves,” she says. The upcoming chocolate festival has 15 craft brands attending — a mix of big players such as Manam and Mason & Co. and small-batch.

Ketaki Churi, co-founder of the Indian Cacao & Craft Chocolate Festival

| Photo Credit:

Raj Pratim Kashyap

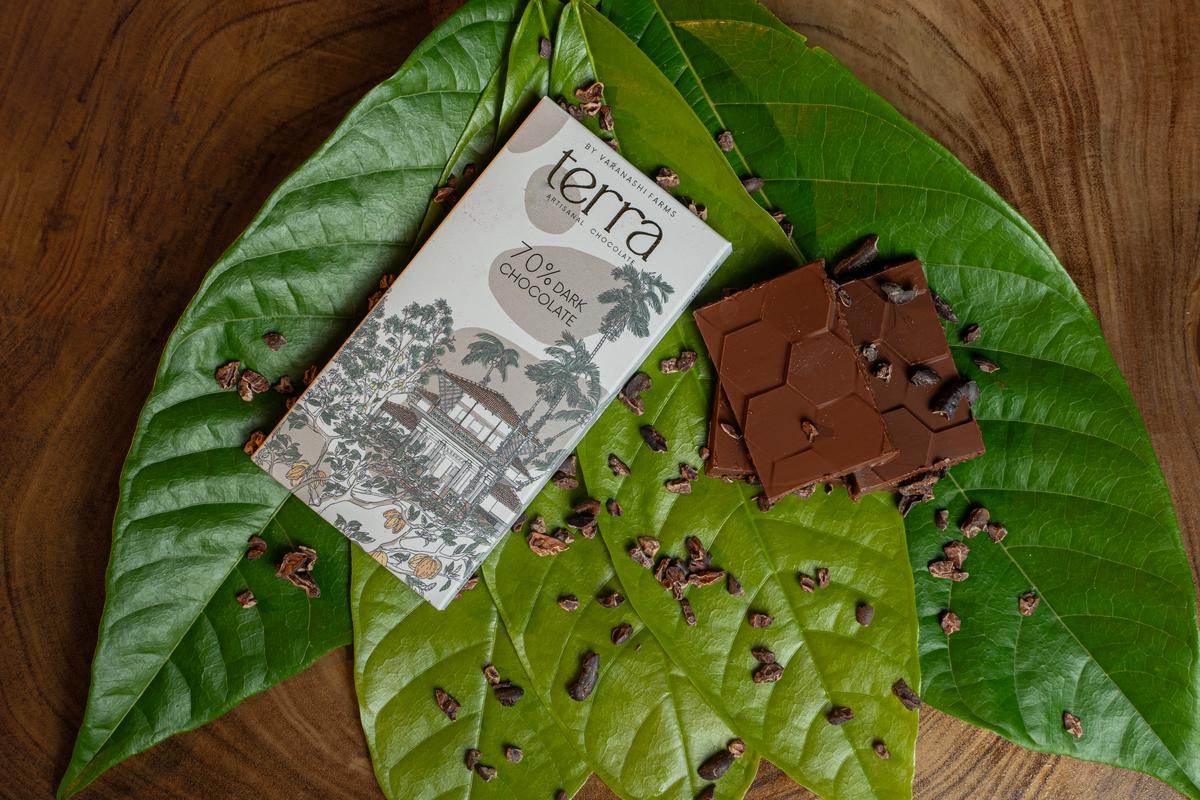

While there are universally-applicable theories to arriving at a wrapped chocolate bar, Churi argues that craft chocolate stands apart because of its attention to the littlest details. “Like, I could decide to turn the cacao beans more often, let the fermentation run for more days, or dry and roast for longer, play with temperature in the service of achieving a certain taste. But in truth, one only understands the profile of the bean once you’ve made chocolate from it,” she says. “These aren’t the kinds of parameters that large-scale, commercial chocolate brands care about.” She is speaking from first-hand knowledge — of making Terra, the in-house tree-to-bar craft brand from Varanashi Organic Farms.

Terra craft chocolate

| Photo Credit:

Keshava Darbhe

Only taste matters

The south of India has several regions where weather conditions are suitable for growing cacao. But despite farms in Kerala, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu, India accounts for only 1% of the world’s cocoa bean production, says Churi.

Indian cacao growers can only supply a quarter of the beans needed by the country’s chocolate market

A reputation for inferior quality and poor handling of harvested beans have also plagued the Indian cacao story. But now newer hybrid varieties and better training are ushering in change. Sai Nair is an engineer turned chocolatier and the name behind Oona, a two-year-old bean-to-bar brand based in Uttarakhand. According to him, if cacao is grown properly, ripened correctly, mindfully fermented, dried with care, and roasted with attention, then it is going to taste good. Nair, who sources his cacao from three farms in Kerala, adds, “We can keep saying chocolate from Latin America or the Ivory Coast is better, but all of it boils down to marketing.” He reasons that “taste is the only thing that matters” and if it fulfils this requirement, then it is good.

Sai Nair of Oona

Nair points to our relationship with mangoes to attempt to pin down our budding romance with Indian cacao. “We have over a thousand varieties of mangoes in India; they are grown in different parts of the country in varied climates, resulting in fruits with an assortment of flavour profiles,” he says. “While people around the world might harp on Alphonso, I’m sure most of us have had a mango that tastes better.” Similarly, Nair urges us “to try Indian cacao beans from different farms and craft chocolate from several makers to find a taste that suits you”.

Oona chocolate

Today, farmers and chocolate makers are nudging each other into bettering each others’ crafts. The word ‘terroir’ is being thrown around in the service of creating legitimacy for Indian cacao. While Nair agrees that cacao beans from two neighbouring farms will taste different because of their farming practices (such as multi-cropping), he adds that it is “the interventions of the farmer during the processing” that creates the tasting notes of a bean.

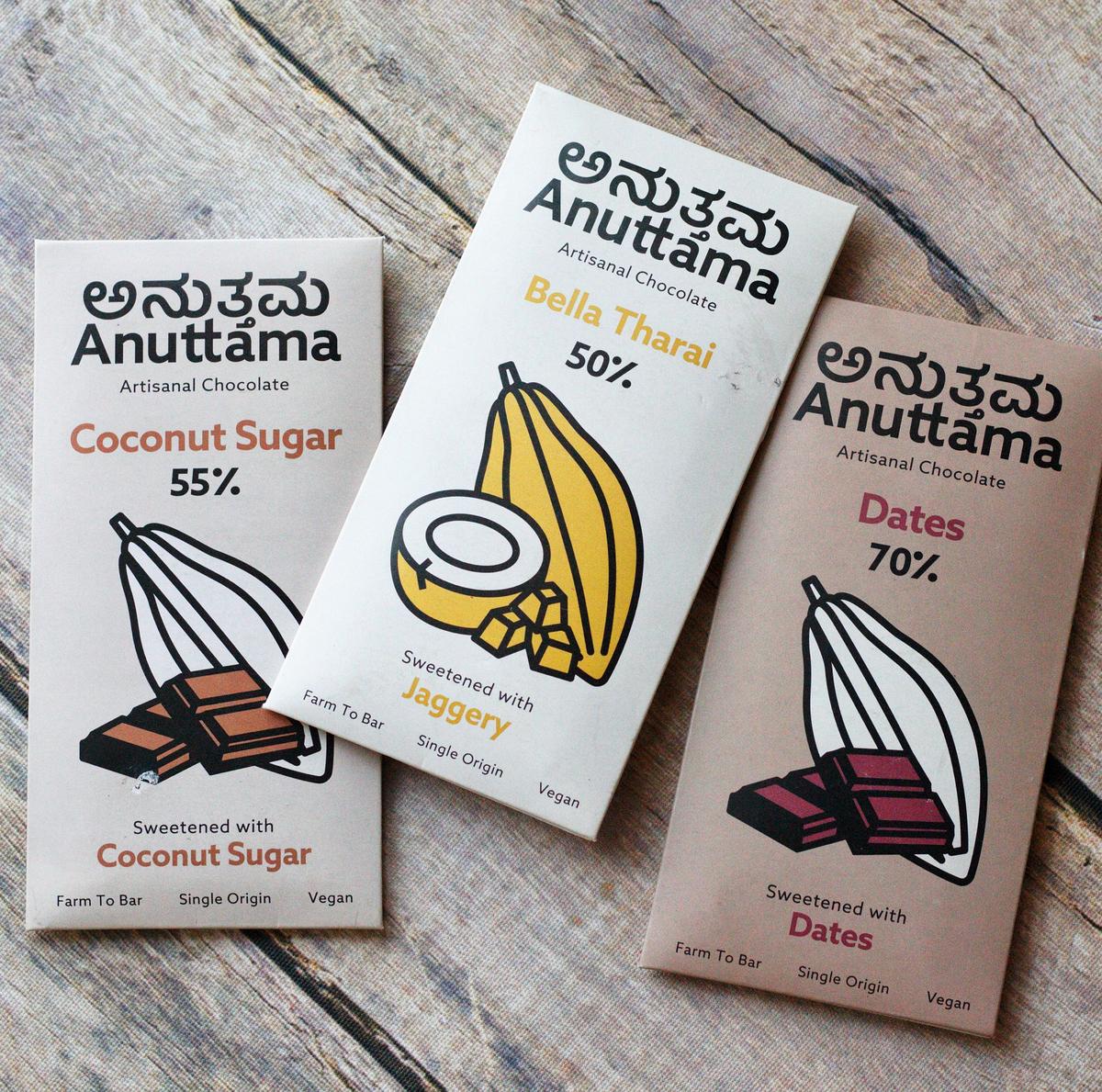

“Farmers are making changes to the growing and processing of cacao [such as removing astringency from beans] as a means to test the value of the crop,” says P.S. Balasubrahmanya, a cacao farmer in Bettampady in Dakshina Kannada District, and co-founder of Anuttama Chocolate. “Five years ago, Indian cacao sold in the wholesale marketplace for around ₹200 a kilo. But the few farmers who sold to craft chocolatiers priced their beans at ₹450 a kilo [because they sorted good beans].” Today, the price has doubled with “cacao beans for craft chocolate going up to ₹1,500 for a kilo” depending on the farm (with better farming practices). If a farmer wants to get greater bang for his cocoa beans, then he has had to learn, adapt and implement newer techniques.

P.S. Balasubrahmanya of Anuttama Chocolate

Anuttama chocolate bars

Kuruvilla Louis, an auditor turned cacao farmer from Kuruvinakunnel Tharavadu Farms in Pala, Kerala, tells me that he recently bought “a small melanger [stone grinder], which can grind four kilos of beans at a time”. The purchase helps him “test our own beans” and learn what processing techniques produce better outcomes instead of waiting “for feedback from the chocolatiers we supply to”. He is also experimenting with the processing of the bean and fermentation. He has been using fruit pulp such as passion fruit and nutmeg, and small-batch craft chocolatiers are willing to try these them. He also sees the melanger as early steps to making “tree-to-bar craft chocolates at our own farm”.

International nod

Bigger, older craft chocolate brands such as Mason & Co, Manam, Naviluna, and Paul and Mike have been slowly making their mark on the international stage — winning awards and finding new markets. Kochi-based Paul and Mike, one of India’s early craft chocolate brands, won the country’s first gold at the 2024 International Chocolate Awards in Romania for their milk chocolate-coated salted capers. They’ve previously won a silver for their 64% dark Sichuan pepper and orange peel vegan chocolate. Manam is another strong contender. Besides winning awards at the Academy of Chocolate Awards UK 2024, the Hyderabad-based craft chocolate brand even earned a place on Time magazine’s World’s Greatest Places 2024.

Raising the bar

Such on-ground mediations by cacao farmers and chocolate makers have begun to pay off. “Everyone is curious, knowledge is being generously shared through channels like chocolate-focused workshops and festivals, and even equipment is accessible in terms of pricing and availability — so there’s a strong craft chocolate ecosystem being formed,” says Anisha Oommen, co-founder of Goya.

Balasubrahmanya sees the coming five years as being exciting for the Indian craft chocolate industry. “Shifts in the market don’t happen overnight, but every year there seems to be an increment in Indian chocolate brands. And cacao growers are increasing too,” he says, speaking from anecdotal evidence, where he has noticed “a lot more farmers in Dakshina Kannada returning to growing cacao after cutting down their trees around five years ago because of low pricing and the lack of a market”.

The Indian Cacao & Craft Chocolate Festival runs Dec. 5-7, at Sabh, Shivaji Nagar, Bengaluru. Details: craftchocolateindia.com

The writer and poet is based in Bengaluru.