Shyam Benegal’s generosity of spirit and time

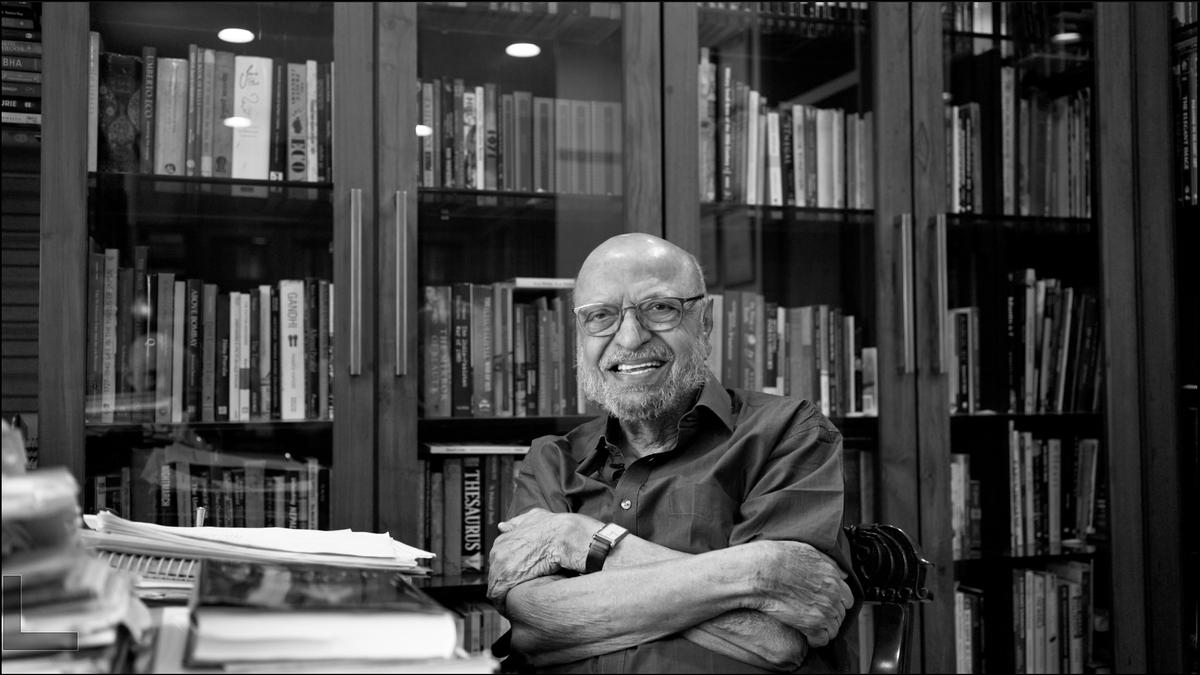

Forty-four years after having known and worked with Shyam Benegal, I finally turned my camera on him. It was January 2023.

I was asking him about his film Mandi (1984), which I had also worked on.

One of my jobs back then was to take photographs of the actors’ costumes, make-up, and jewellery. Mandi was in colour but we didn’t have a budget for a Polaroid camera. I was therefore handed a camera with a few rolls of black-and-white film.

Those photographs lay in a box for 40 years. After the pandemic, shifting houses, and sorting boxes, I rediscovered them. And thought of making a film about photographs and memory.

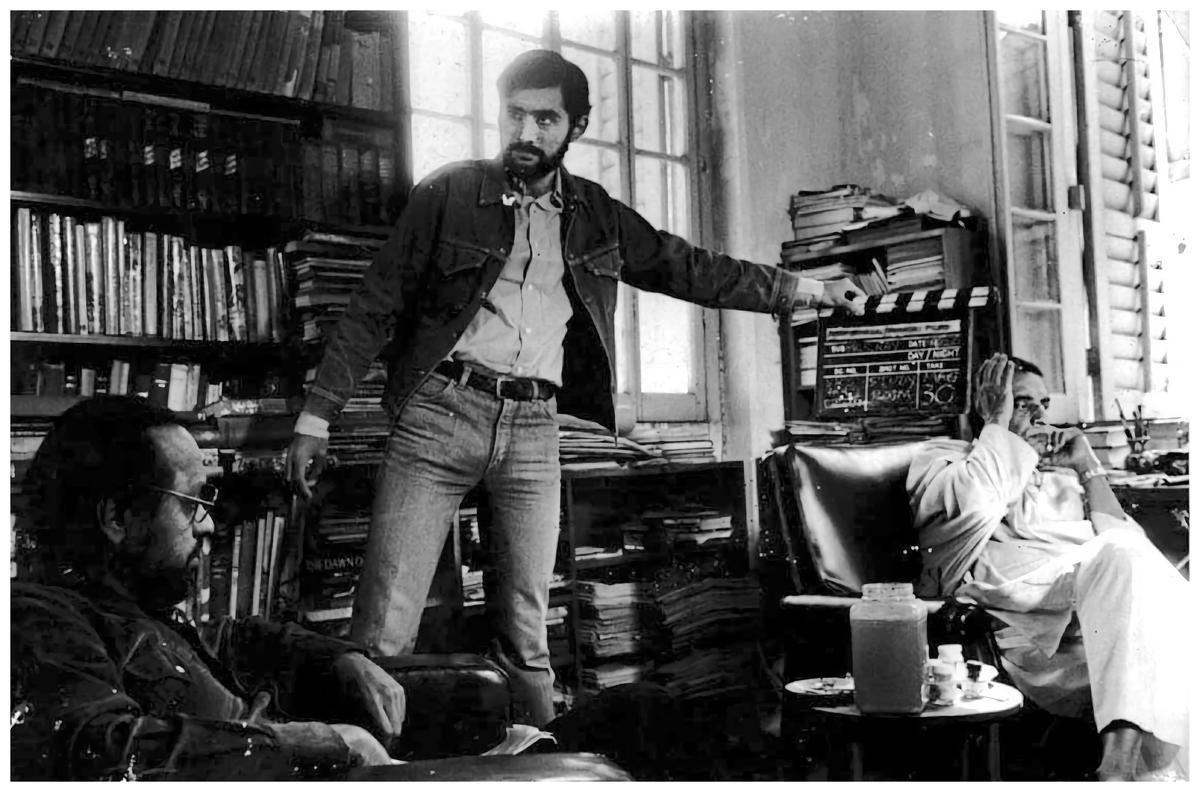

(L-R) Shyam Benegal, Dev Benegal, and Satyajit Ray on the set of the documentary Satyajit Ray

“I haven’t talked about the film or discussed it for many years now… the memories have faded,” Shyam said when we met in January. As my camera rolled, he spoke about its origins, the filming, all the way to its reception. By then, he was already quite unwell. Yet his memory was razor-sharp.

“It worked well because of the actors. They were part of the creative side of the film… not just their performance, but they all contributed to the story.” The movie starred Shabana Azmi, Smita Patil and Naseeruddin Shah, among others.

Shyam was always the consummate director, never once taking credit for the world and characters he created. There was none of the auteur hubris in him. His filmmaking style was always collaborative. He encouraged his actors’ constant questioning.

This openness and collaboration were the greatest lessons for any young filmmaker.

Unveiling another India

Ten years after working on Mandi, I made my first feature, English, August. After its screening, in the foyer of Metro Cinema, Shyam said, “I was nervous when it began. I was wondering how you carry that style through the film.” And then, to my relief, he smiled.

Shyam Benegal

| Photo Credit:

Dev Benegal

Mandi was a satire; in its jazzy, baggy style, it was a searing indictment of society and its antiquated morality. Based on a true incident — when Motilal Nehru was running the Municipal Corporation in Allahabad — it was set in a fictional town, a lot like the fictional town of Madna in my film English, August.

I worked on Kalyug (1981), Arohan (1982), Mandi (1983), and Satyajit Ray (1984) with Shyam. Working with him and his collaborators was a greater education in every facet of cinema than any formal classroom. Ashok Mehta, Shyama Zaidi, Satyadev Dube, Kamat Ghanekar, Bhanudas Divkar, P.G. Mulay, Vanraj Bhatia… the list is endless.

His office, Shyam Benegal Sahyadri Films or SBSF as we called it, was making feature films every year alongside commercials, which kept the atmosphere electric.

What set him apart was his breadth of knowledge. There was almost no subject into which he did not have a deep insight or an original perspective. He truly was a Renaissance man.

He never believed in the industrial way of filmmaking, segmented and compartmentalised. Instead, he encouraged us to work on every aspect of it. He was always walking that tightrope; wanting to engage the audience, while also fearlessly experimenting with form. Cinema, as a medium, was to him almost infinitely malleable.

Through his films, Shyam unveiled another India. His films were not entertainment. They were visceral, raw, and determinedly designed to be uncomfortable. Power, politics, sex, caste — these were his areas of engagement. Film was, for him, part of the process of social re-engineering. You could not deny the discomfiting realities of his filmic world. He bared uncomfortable truths, the harsh realities of contemporary India, particularly an India that seemed to him to have gone off the rails.

Few have understood the language of cinema as well as he. He spoke through his films, and the thread that runs through his body of work is that filmmaking is, above all, an act of social responsibility. We should not forget: he was a young man of 15 at the dawn of India’s independence, and the newly fashioned idea of a free, democratic, and secular country was, for him, as it was for others of his generation, as seminal as it was formative.

Unabashedly a Nehruvian optimist, he believed that cinema, more than any art form, could convey the idea of a complex, pluralistic nation — precisely what Jawaharlal Nehru described as an “ancient palimpsest on which layer upon layer of thought and reverie had been inscribed”. Cinema was, in his understanding, a great leveller, utterly democratic, and uniquely accessible across geographies and cultures. In the darkness of a cinema hall, everyone is equal.

For this reason, censorship worried him. He could never digest the idea that a handful of people could decide what the rest of the country should see. “Let the people decide what they want to see,” he would say, as we were preparing a film to submit to the censor board.

Easy laughter and camaraderie

New York was his and (wife) Nira’s favourite city. Our times there were special. We would slip out of a side exit from some insufferable ceremony at a film festival, and I would take them to a small dumpling restaurant in Chinatown. Friends joined in. The conversation went on late into the night. That’s what he liked the most: the conversations and the easy laughter and camaraderie of those bound together by art.

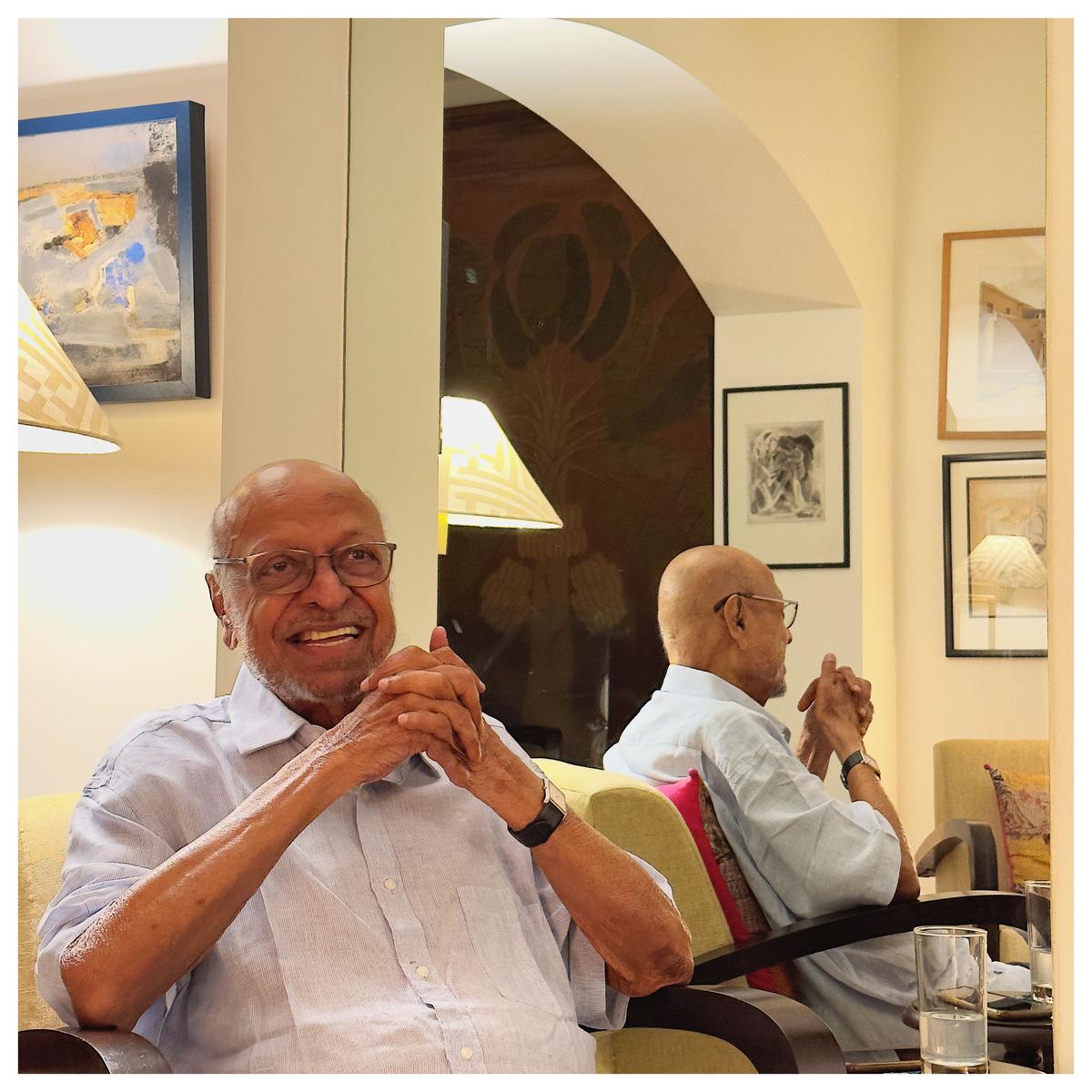

The last few years were very intimate. The four of us — Shyam, Nira, his daughter Pia, and I — would get together in the evening. What was planned for an hour would stretch to five. Again, laughter was at the heart of it.

(L-R) Shyam Benegal, Pia, Nira and Dev Benegal

In 1982, the Films Division asked him to make a film on Nehru and another on Satyajit Ray. Shyam asked which film I’d like to work on. Without a moment’s hesitation, I chose the latter. The film on Satyajit Ray took longer than expected. I was in London working on Girish Karnad’s Utsav. Jennifer was ailing, and Shashi Kapoor had asked if I could stay back and work on the subtitles of 36 Chowringhee Lane. I could not say no. When I finally returned to India, Shyam called to say the Ray film was not complete. He was waiting for me to get back to work.

I dived right in. There were hours of 35mm film rolls to edit. From research, to being on set while we filmed, to looking under the beds of producers to locate the negatives of Ray’s films, to the final sound mix, colour-grade, and delivery of the print — it was totally hands on. I had a huge responsibility, and there were times when I wondered if I could live up to Shyam’s standards.

When we finally got a VHS of the film, Shyam took my copy and wrote a beautiful inscription on the label. It read: “This film is as much yours as it is mine.”

I am not alone in this thinking. Filmmakers and filmgoers in India carry a bit of Shyam’s world with them, wherever they go. Beyond his art, he showed us the value of making moral choices. In his work, and in the way he chose to work, there are lasting lessons and inspirations to artists everywhere, and yes, activists in need of inspiration to stand firm against the wrongful tide.

But here’s the thing: the mark of a truly great artist is generosity — of spirit, of time, of teaching, of friendship. Shyam was, from first to last, a friend and a mentor who kept on giving. He will be with us for the rest of our days.

The writer is an award-winning filmmaker known for English, August. His film Still, Life on Shyam Benegal and the memory of Mandi will be out this year.

Published – January 03, 2025 10:52 am IST