The Hindu Lit for Life | Why geography matters to Abraham Verghese, author of The Covenant of Water

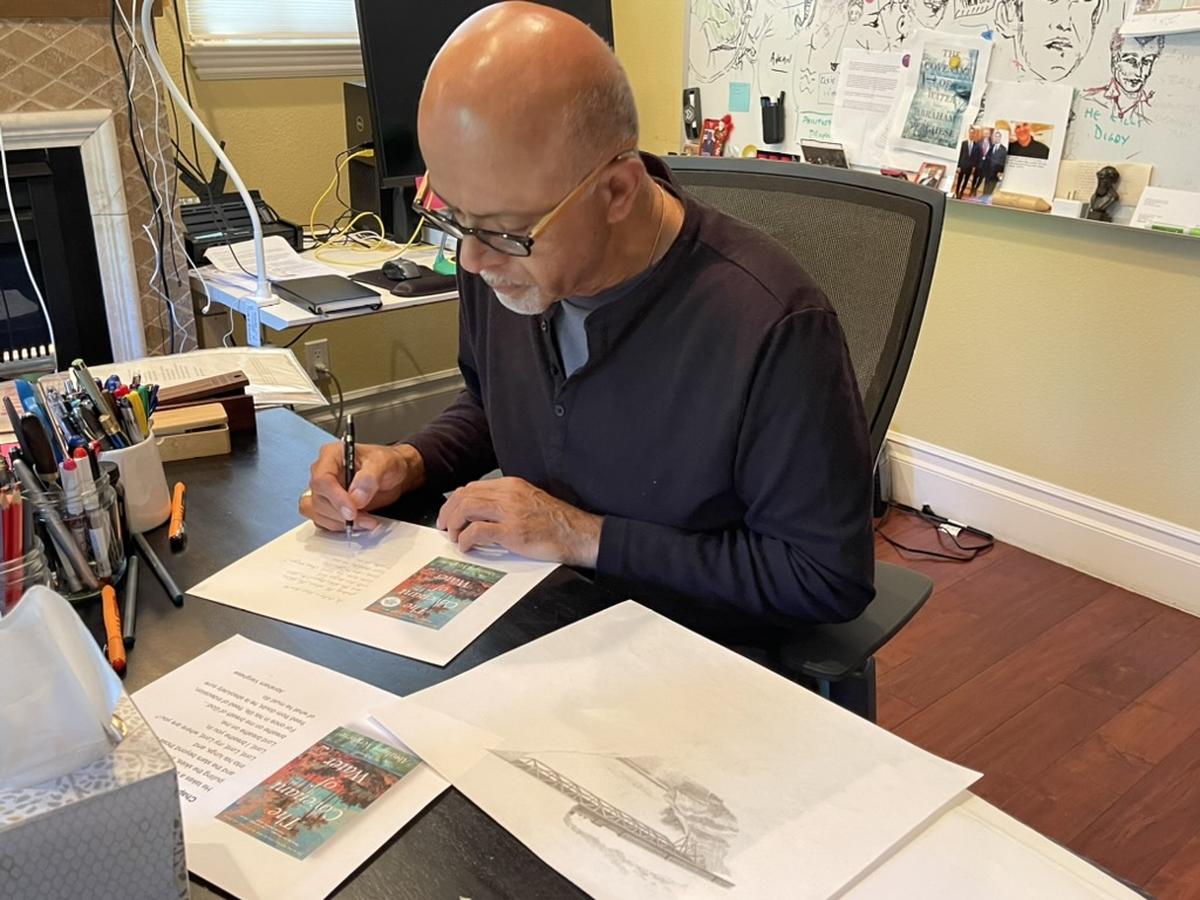

Abraham Verghese will inaugurate The Hindu Lit for Life 2025 in Chennai on January 18, 2025.

| Photo Credit: Christopher P. Michel

Physician and author Abraham Verghese often says that every change in geography has shaped his destiny. His parents moved from Kerala to Ethiopia, where he was born. Later, as there was civil unrest in Ethiopia, he followed them to the United States, where he practises medicine, teaches, and writes. Verghese’s ancestry and his experiences in the two countries where he has lived have formed the basis of his four critically-acclaimed books.

In his fourth and latest work, The Covenant of Water, published last year, Verghese narrates an epic story spanning three generations in Kerala. Oprah Winfrey has bought the rights to adapt the book info a film. Ahead of The Hindu Lit for Life 2025, which the author will inaugurate in Chennai on January 18, Verghese discusses why he always wanted to write fiction and the difficulty of mining one’s own life for material. Edited excerpts from an email interview:

You have written two memoirs. Why did you feel the need to document your life?

In the mid-1980s, when I was living in a small town in Tennessee, working as an infectious diseases specialist, I saw more patients with HIV than was predicted for a rural town of 50,000. I realised I had stumbled onto an American paradigm of migration: young men who had left their small towns because they were gay were now returning decades later, having contracted the virus, and having cared for partners who had passed.

At the time, AIDS was considered an urban phenomenon. I wrote a scientific paper describing the paradigm, but I felt it never quite captured the heartache of their journey, or the grief of their parents, or my own grief at seeing this again and again. I became a writer to tell that story — through fiction, or so I thought. But it turns out that non-fiction is much more in demand by publishers than fiction, because non-fiction sells predictably: if something really happened, we all have an inherent interest. So that story became my first book, My Own Country (1994). I thought I was telling the story of the small town and HIV, but inevitably, since I was a character, it was also a memoir.

At the time I was writing the book, I was also living through an experience with one of my medical students, another extraordinary true story. Publishers were anxious for me to write another non-fiction book when I finished the first one, and the story that became The Tennis Partner (1998) seemed an easy way to do so. However, I really always wanted to write fiction, so after two memoirs I have not gone back to non-fiction. It isn’t easy to mine your own life for material.

Memory is a tricky thing. In memoir writing, how do you ensure that you have got things right, especially when you’re writing about emotional episodes from your life?

I think readers understand that memory is unreliable, and that all writing is in a sense a kind of artifice. If you confine yourself not to your memories but to what can be documented to have happened, and only to dialogue exactly what was said… well you have a very dry book, or else it is a newspaper account. Instead, just as when you are sitting with friends and recounting what happened to you, your listeners get your best recollection and they know it comes with all your biases, and with your propensity to exaggerate or else to under-report.

You often talk of how every change in geography changed your destiny. What other factors do you think changed your destiny? And can destiny be changed at all?

Geography matters greatly. But so do the choices you make at different crossroads in your life. Ultimately, I think life is ironic, and dependent on luck, fate, happenstance, etc. I never intended to be a writer so the fact that we are having this exchange is an example of how life is ironic. I chose infectious diseases as my specialty in medicine before AIDS came along; colleagues in other fields perhaps felt sorry for me. The AIDS experience was the hardest thing I ever did, emotionally and personally; but it made me a writer. So, in short, I think our destinies are shaped by events beyond our control.

‘The Covenant of Water’ took you 14 years to write. When you’re working on a book for so long, does your writing or the story change? And if yes, how do you address that?

I’m never in a great hurry to follow one book with another and another. This explains why the “canon” of my works is tiny. And I have a busy day job. But the job allows me the luxury of not having to churn out one book after the other to pay the bills; it has given me the luxury of being able to take my time. None of this I realise is a great explanation. The truth is I am slow, lazy, a great procrastinator. And despite every outline I make when I begin a book, in the act of writing, strange things happen — call it the muse, or the subconscious — and I wind up departing from the outline. Sometimes that detour is just the right thing; at other times you discover after six months of going in that direction and accumulating hundreds of pages, that you have come to a dead end. So, you back up and start again.

You have written quite a bit about your family. Is there a constant process of inclusion and elimination of stories, details, or memories during the writing process?

I think all stories are about family, ultimately. Tolstoy says, “All happy families are alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” And so, families — fictional or real — are inevitably good stories. As for the process, I think revision is the real skill of writing. And I think it is fatal, with certain exceptions, to show anything to anyone but your editor. Family can love your work even when it is bad. Or else they can bruise your ego when it really is bad, and they say so. At a later stage in the development of a piece, both my partner Cari and my older brother George are extremely helpful in different ways in the process.

Fiction, you say, stops time. What is the one book of fiction you read this year that truly stopped time for you?

Right now, I am reading Paradise by Abdulrazak Gurnah. The book is extraordinary and when I am in its pages, I disappear; time stops.

radhika.s@thehindu.co.in

Abraham Verghese will be at The Hindu Lit for Life (January 18-19) in Chennai. Click here to register.

Published – January 03, 2025 09:53 am IST