The School of International Studies at Jawaharlal Nehru University celebrates its 70th anniversary

The School of International Studies (SIS) at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) will celebrate its 70th anniversary next month. With two alumni — Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman and External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar — in the Cabinet Committee on Security, the SIS has has been a furnace where ideas meet power, where scholarship shapes strategy, and where India’s intellectual sovereignty is forged.

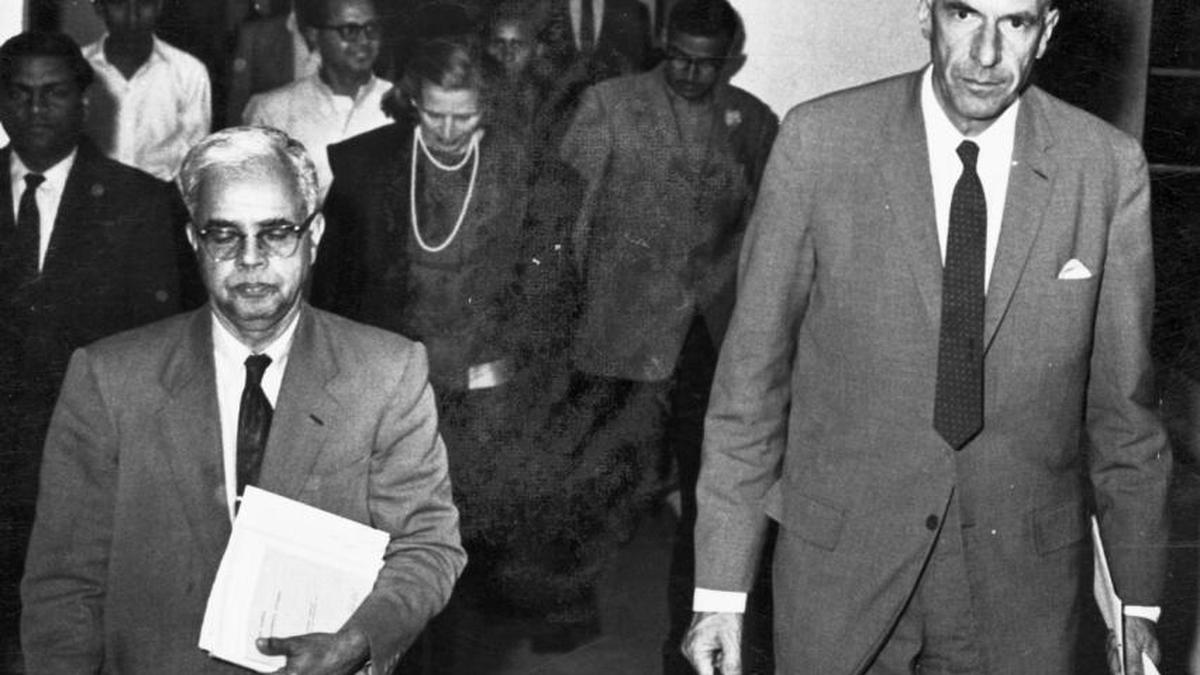

The institution began its journey in 1955, when India was barely a decade old. Its leaders had the foresight to realise that diplomacy could not be sustained on instinct alone. India needed an institution to train minds capable of interpreting the world, not just mimicking it. Thus was born the Indian School of International Studies under the Indian Council of World Affairs. Hriday Nath Kunzru and Tej Bahadur Sapru gave it intellectual legitimacy and Angadipuram Appadorai gave it structure. Its inauguration by the Prime Minister and the Vice President signalled that the Republic saw ideas as essential to power. When SIS merged with the Jawaharlal Nehru University in 1970, Vice-Chancellor G. Parthasarathi dreamed of creating an “Asian equivalent of the Kennedy School”. That dream was not hubris, but an assertion that India could produce an institution that was both academically rigorous and policy relevant.

H.N. Kunzru, co-founder of the School of International Studies.

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu Archives

From the outset, SIS distinguished itself in two ways. First, it embraced area studies at a time when most of the world still privileged Euro-American frameworks. Its scholars immersed themselves in Asia, Africa, Latin America, and the neighbourhood, ensuring that India’s gaze was not provincial but planetary. This was intellectual decolonisation in action: scholarship that gave India an independent map of the world. Second, It also combined theory with practice; its classrooms trained diplomats, policymakers, and future ministers. Its faculty shaped debates on non-alignment, nuclear policy, South Asian regionalism, multilateralism, international law, conflict resolution, and the Global South.

When India confronted the Bangladesh crisis in 1971, when New Delhi grappled with the Sri Lankan imbroglio in the 1980s, and when we debated the nuclear option in the 1990s, SIS scholarship provided clarity and context. The journal International Studies, launched in 1959, gave the Global South a platform to think in its own terms.

The post–Cold War era forced new thinking. Globalisation, nuclear restraint, peace processes, and regional integration demanded fresh paradigms. SIS responded by combining insights from international debates with India’s traditions. From Kautilya’s Arthashastra to the Mahabharat, from Ashoka’s dhamma to the policy of non-alignment, SIS drew on India’s civilisational depth to craft frameworks that were at once rooted and global. It was never about mimicry; it was about originality.

But anniversaries are not only for celebration; they are also moments for reckoning. The conditions that nurtured SIS — public funding, intellectual autonomy, and an open global order — are now fraying. The corporatisation of higher education, and shrinking intellectual spaces threaten its plural ethos. Algorithms and sound bytes privilege immediacy over depth, fragmenting the very fabric of scholarship.

Yet, the demands on institutions like SIS have never been greater. Climate change, pandemics, Artificial Intelligence, and the geopolitics of technology demand precisely the mix of theory and practice that SIS was designed to offer. The rise of China, the uncertainties of globalisation and the return of great power rivalry require India to generate its own frameworks. Western theories, however sophisticated, cannot substitute for Indian perspectives rooted in India’s experience. In short, knowledge about the world is itself a form of power. SIS has, for 70 years, ensured that India does not outsource this knowledge. Its legacy is not only in its alumni lists, but in the ideas it has produced: non-alignment as grand strategy, South Asia as a living laboratory, nuclear realism as statecraft, multilateralism as democratic aspiration, and the Global South as a community of thought.

The future demands clarity of purpose. Three imperatives stand out. First, SIS must renew its pioneering role in area studies — South Asia, West Asia, Africa, and the Indo-Pacific remain turbulent theatres demanding original insight. Second, it must continue to blend theory and practice; engaged with policy, but uncompromising in its defence of intellectual independence. Third, it must globalise Indian international relations, ensuring that perspectives rooted in our civilisation enrich world discourse rather than echo it.

For me, this milestone is not merely institutional but personal. I arrived at SIS as a wide-eyed and eager young student from Srinagar. In its classrooms, I found the diversity of India and the excitement of global debate. Later, as a teacher and now as dean, I have witnessed its triumphs and its trials from within. That journey — from student to scholar to dean — has only deepened my conviction that SIS is not just a school but an idea that India must understand the world in its own voice, interpret its own experience, and think for itself.

If SIS can preserve its independence and plural spirit while innovating boldly, it will not only commemorate 70 years but also shape the next 30. For an institution that has already given the nation so much by way of statesman and ideas that have travelled across the world, nothing less should be expected. After all, SIS@70 is not just an anniversary; it is a reminder that knowledge, when rooted in independence and imagination, is the truest form of power.

The writer is Professor and Dean, School of International Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi.

Published – September 19, 2025 03:37 pm IST